Written by: Naina Bhargava

In April, the World Economic Forum released the The Global Gender Gap Report 2021, in which India was ranked at a dismal 140 out of 156 countries. We’re down 28 positions on the Index in 2020. This year’s report tells us that it’s going to take South Asia, wait for it, 195.4 years to bridge the gender gap on four fronts – political empowerment, economic participation and opportunity, education and health. As the most populous country in the region, India has single-handedly brought the average down for the rest of South Asia.

Why the Need for Gender Safety Audits?

Briefly put, women in India are far from receiving opportunities to participate in the labour market, and also do not have the representation needed to make a difference politically. The first fact shouldn’t come as a surprise as Indian women’s participation rate in the labour market has been on the decline consistently for about a decade now, currently standing at an abysmal 22.3%.

As for the report, India has closed only 32.6% of the gender gap when it comes to economic participation. On the sub-index that measures political empowerment, share of women ministers have gone down from 23.1% to 9.1%.

These numbers speak for themselves, don’t they? Unfortunately, they tell us a story that goes beyond just India. The fact that we have a Global Gender Gap Report released every year since 2006 should tell us that 21 years into the 21st century there still remains a lot to be done to bring cisgender women across the world on an equal footing with their male counterparts. Gender safety audits are an important step to achieve this equal footing.

From Invisible To Visible

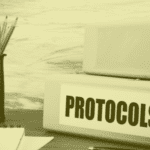

Taking the conversation ahead on numbers and gaps that show how women across the world have been excluded and their lived experiences ignored, kept aside or forgotten. In this article, I review some key parts of the 2019 book Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias In A World Designed For Men by Caroline Criado-Perez.

In the book, Perez exposes government and social systems that have been built on the assumption that the world, by default, has been for men. She argues that lack of sex-disaggregated data on a range of issues have made it harder to track violence against women, unpaid care work, and how public spaces like workplaces, transportation systems keep women at a disadvantage on a daily basis. The book covers a lot of ground but for this article we will limit Perez’s research and reflections to the workplace.

Why Is It So Cold All The Time?

A question that women in corporate offices often ask themselves – little do they know that they’re shivering because the temperatures weren’t set for them – they were set for men. In her chapter titled, ‘The Henry Higgins Effect’, Perez shares that the “formula to determine standard office temperature was developed in the 1960s around the metabolic resting rate of the average 40-year-old, 70 kg man.”

It doesn’t just end with the fact that the formula was only developed keeping men in mind. Recent study cited by Perez found that the metabolic rate of young adult females doing the same kind of work in the office is much lower. Due to the gender data gap, office environments are at least five degrees too cold for women.

This example are one among many that show how workplaces were built with the assumption that they were only going to be used by men. Some other infrastructural gaps that confirm this statement are: “doors that are too heavy for the average woman to open with ease, to glass stairs and lobby floors that mean anyone below can see up your skirt, to paving that’s exactly the right size to catch your heels.”

These examples are for spaces that are accessed by folks with some degree of privilege. What about women working in hazardous or poor working conditions? Perez illustrates with several examples on how neglecting or omitting women from the scope of research could adversely affect their health. From long term chemical exposure in nail salons, intense weight lifting as carers for the elderly to wearing ill-designed vests and uniforms to women in the military.

In India, women working at construction sites and garment factories, among others, have poor working conditions and are also vulnerable to sexual harassment. Not only would gender safety audits to fill such gaps in the Indian context prove to be useful but also a general awareness on how workplaces exclude by design can help leaders, both in the public and private sector, draft and implement more inclusive policies.

A Lot Of Working For Free : Gender Safety Audits the Way Forward

Patriarchy expects that women to be caregivers and wants men to be breadwinners. Today, we’re living a hybrid version of that diktat – men are still breadwinners and women are still caregivers but a lot of them are also breadwinners now. That only means that women have more work than before – one in the public space that pays them less than men (Indian women are paid 19% less), and one in the private space where they take care of their homes, their partner, children and the elderly – for free.

Perez rightly says, “There is no such thing as a woman who doesn’t work. There is only a woman who isn’t paid for her work.”

In the chapter titled ‘The Long Friday’, Perez explains in great detail what ‘work’ at home and ‘out of home’ really looks like for women. In the formal workforce, women are paid less, they encounter glass ceilings that restricts their career growth, and policies on maternity leave and childcare are often not suitable enough for them to carry on full time. At home, depending on their socioeconomic location, it is mostly women who perform a large share of domestic work, including caring for the family.

In the book, Perez cites pertinent data on how much more women are doing at home: “Globally, 75% of unpaid work is done by women, who spend between three and six hours per day on it compared to men’s average of thirty minutes to two hours.”

This global projection by Perez matches domestic data. In 2020, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation released a survey on ‘Time Use’, wherein they found that women spend 299 minutes on unpaid domestic work – cooking, cleaning, household management as compared to men, who only spend 97 minutes.

According to a survey published by the International Labour Organisation in 2018, the biggest hurdle stopping women from entering, staying, and advancing in the labor force is unpaid care work. In 2018, 606 million working-age women reported being unable to engage in the labor force due to unpaid care jobs.

Perez argues that the only way more women could join, stay and grow in the formal workforce, if only provisions were made to acknowledge, reimburse and redistribute unpaid care work.

These are only two selected insights from the book. If you would like to dig deep, the four chapters in the second section of the book is where Perez discusses everything about the workplace. It’s a must read for everyone trying to get a better understanding of the gendered nature of our world.

About the author: Naina is a final year student at Miranda House, University of Delhi.

Ungender Insights is the product of our learning from advisory work at Ungender. Our team specializes in advising workplaces on workplace diversity and inclusion. Write to us at contact@ungender.in to understand how we can partner with your organization to build a more inclusive workplace.