Data Wrap: Women in the Boardroom

Board diversity, including the presence of women, is an essential element in the development of organizations. Diversity is said to improve financial performance, stock market performance, and non-financial performance as well.

In this Data Wrap, we will look at the percentage of women in the boardroom globally & in India. We will also analyze the causes of the lack of diversity on boards of directors or at other top levels of enterprises and present strategies to increase and manage diversity.

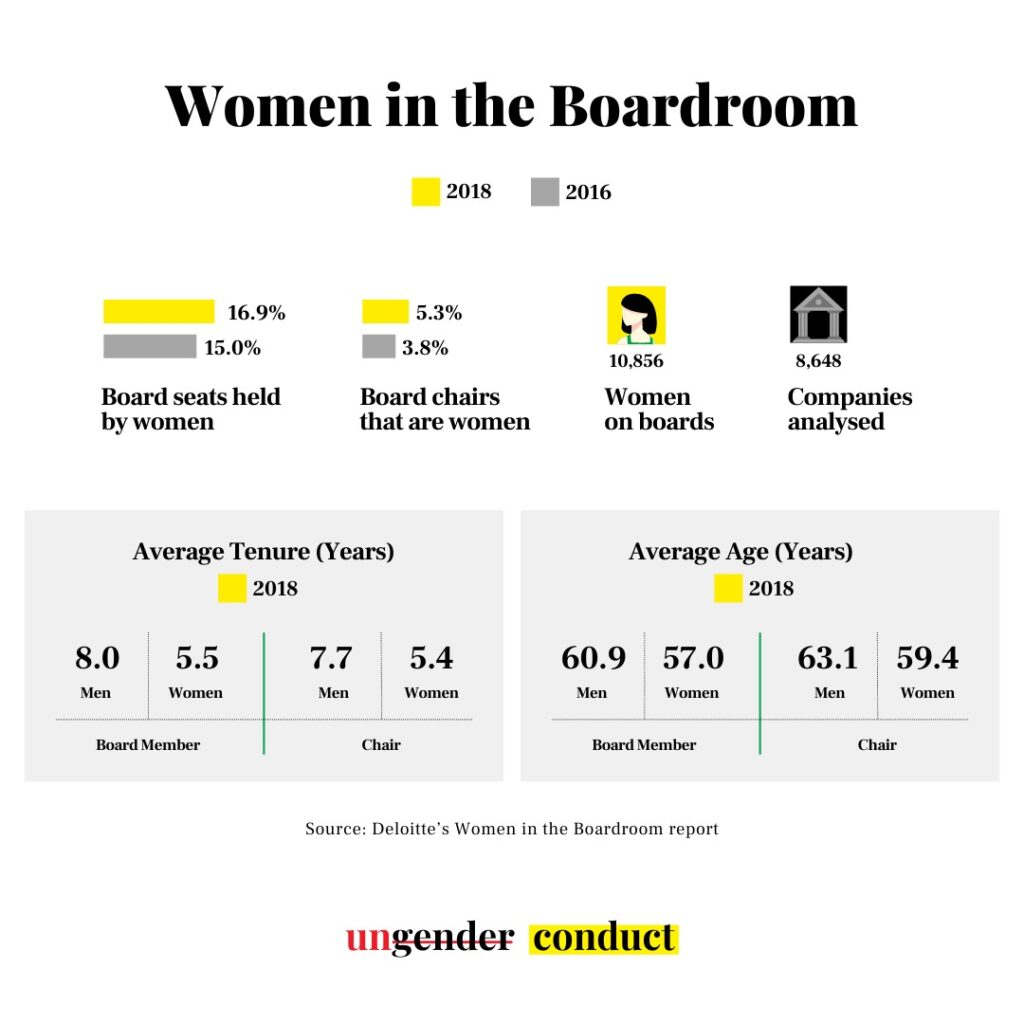

Deloitte’s Women in the Boardroom report shares the latest statistics on global boardroom diversity, exploring the efforts of 66 countries to increase gender diversity in their boardrooms and features insights on the political, social, and legislative trends behind the numbers.

Highlights include:

- Women hold 16.9 percent of board seats worldwide, a 1.9 percent increase from the previous edition.

- Women hold only 5.3 percent of board chair positions and 4.4 percent of CEO roles globally.

- Women hold 12.7 percent of CFO roles globally – nearly three times that of CEO positions.

Despite numerous studies that have prompted regulatory, shareholder, activist, and individual initiatives to ensure equal opportunities for women and some measurable improvement, progress is still much too slow with only a 1.9 percent increase.

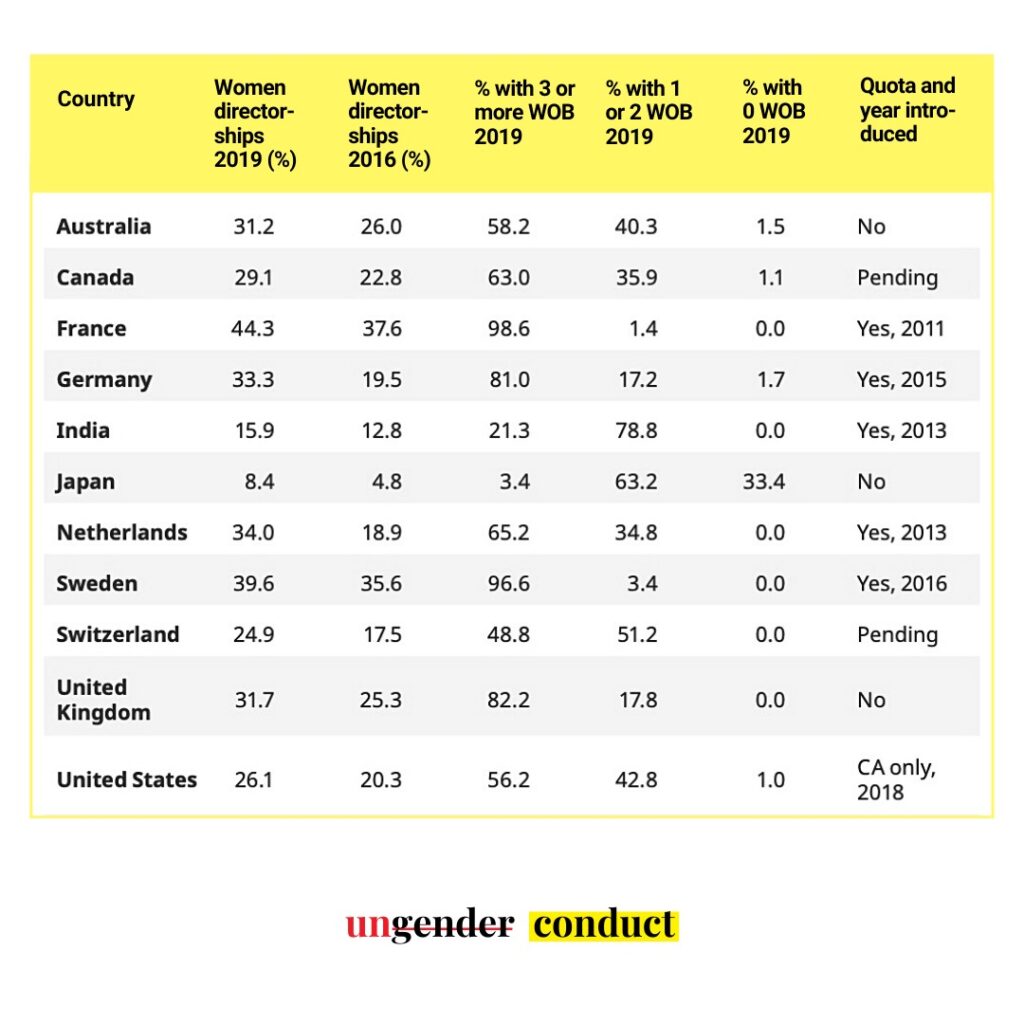

Table 1. shows the impact of having mandated legislation for promoting women in the boardroom.

Source (Catalyst, 2020)

As shown in the above table, several European countries have introduced a binding law, imposing quotas for female board members and sanctions in case of quota non-compliance.

France adopted a law in January 2011 imposing gender diversity – of 20 percent by 2014 and 40 percent by 2017 – on the boards of directors of listed companies and companies with more than 500 employees with assets or revenues exceeding 50 million euros. Failure to comply with the quotas invalidates director appointments and results in the non-payment of director fees.

Other countries, like Canada, opted for a more moderate approach requiring companies to include diversity policies in their governance codes or requiring them to disclose details on the composition of their board of directors with regard to gender under the principle “comply or explain”.

Table 1 suggests that quotas may be more effective than less constraining approaches. However, whereas gender diversity in the boardroom may be attained more quickly with binding legislation, the depth of such transformation may be questionable.

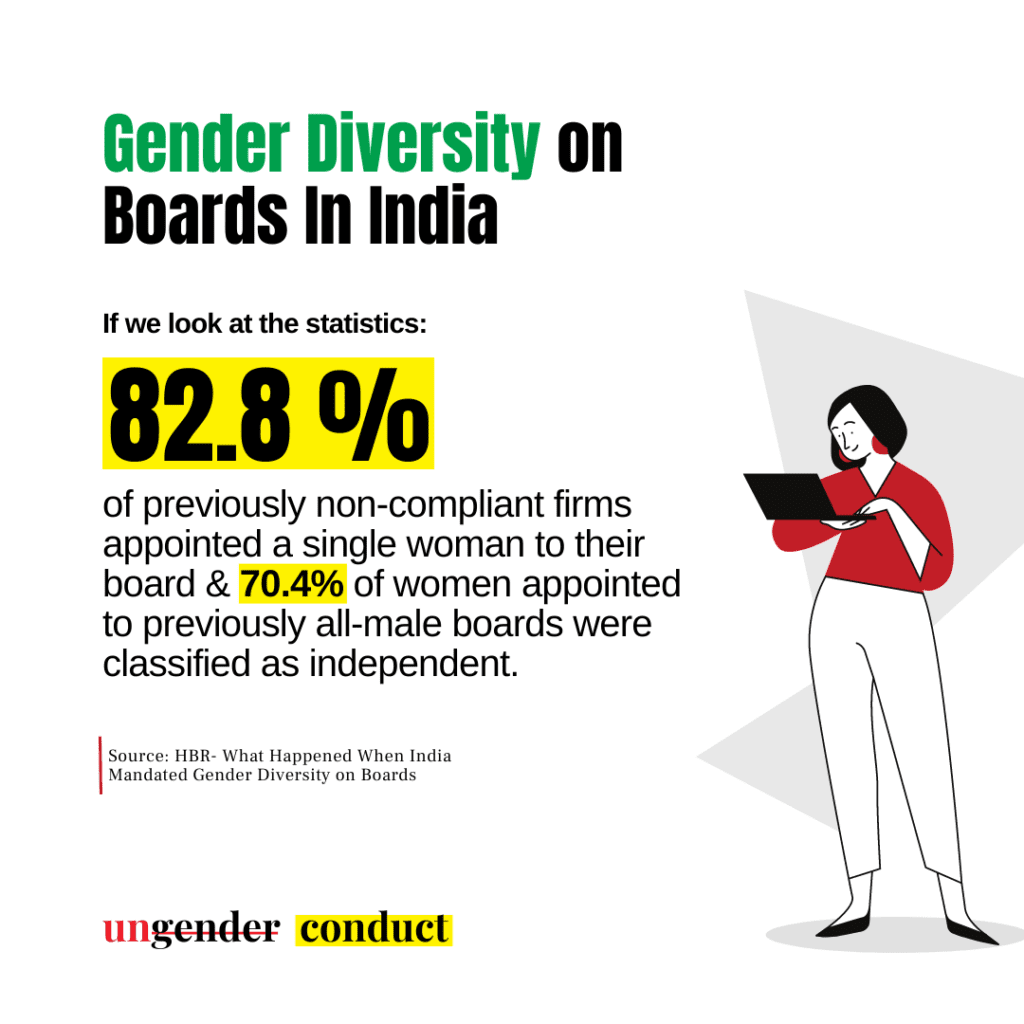

In India, Listed companies and other large public limited companies are required to appoint one or more women to their boards under the Companies Act of 2013. Vacant board seats previously held by the female directors are required to be filled by other females within three months of the vacancy or by the company’s next board meeting whichever is later.

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) recently introduced a provision under its listing requirements addressing gender diversity. Boards of the largest 500 listed companies, as ranked by market cap, were required to have at least one female independent director by April 2019.

Although more rapid and statistically significant increases in the proportion of women on boards may be observed as a result of quota imposition, a broader and more robust analysis of how the presence of women on boards improves decision-making and corporate governance could better justify legislation.

Reasons for the slow progress despite regulatory initiatives are multiple and complex. To begin with –

Corporate Culture: Does it acknowledge gender differences?

If the goal is a greater diversity of thought, manners, and approaches, then gender differences should be emphasized and not downplayed.

Kanter highlighted (1993): “people in power (mostly men) mentor, encourage, and advance those who are most like themselves. Not surprisingly then, the handful of women who actually do achieve senior ranks in organizations usually resemble the men in power. They have to identify with and emulate the masculine model in order to progress in the organization.”

Hence, the organizational environment or culture may be partly responsible for lack of diversity in many corporations (Hillman, Shropshire, and Cannella Jr., 2007; Fitzsimmons, 2012). This may be even more visible in certain fields known as being male-dominated, such as engineering or science and information technology, where conscious or explicit biases may lead to overt discrimination.

Unconscious biases: Changing hardwired mindsets

Invisible biases exist across all sectors. Such implicit associations or attitudes about age, gender, sexuality, race or disability operate beyond our control, alter our perceptions and influence our decision-making and behaviour towards persons or social groups (Mattia, 2018). For example, some may believe that younger people have less to offer in the workplace.

Others may unconsciously associate women with childcare and men with executive roles, or people of different ethnicities with negative or positive personality traits.

While most individuals consciously know that these are largely unsubstantiated generalizations about large groups of people, our brains have unconsciously formed associations from all experiences and information we have encountered since early childhood. Unconscious biases are more prevalent than outright sexism or racism but can be just as damaging.

The Road Ahead

An understanding of each personality difference between different fractions of the male and female population could help to better develop “gender intelligent strategies” and encourage both men and women to thrive, rather than to force everyone into a system that tends to motivate those with specific personality traits.

Further, mentorship, championing, and networking can change negative perceptions and shine a brighter light on an untapped pool of under-represented talent.

Lastly, setting clear diversity objectives is highly recommended regardless of the improvement approach selected. Setting targets is a part of everyday business. In the same way, as is true when setting financial or other operational targets, establishing realistic gender diversity targets helps ensure that organizations treat gender balance as a core business issue. What gets measured gets done.

About the author: Vanita is a lawyer and Lead – Research & Communications at Ungender. She writes extensively on building inclusive workplaces, gender issues, social inequalities, and public policy.

Ungender Insights is the product of our learning from advisory work at Ungender. In our initiative to build inclusive workplaces for all individuals, we continue to educate and advise leaders on the same. Write to us at contact@ungender.in to know more about our advisory services.

Read our insights about diversity, legal updates and industry knowledge on workplace inclusion at Ungender Insights. Visit our Blog.

Sign up to stay up-to-date with our free e-mail newsletter.

The above insights are a product of our learning from our advisory work at Ungender. Our Team specialises in advising workplaces on gender centric laws.

or email us at contact@ungender.in